In Part I, we discussed how common homonyms can be in Japanese (over a third of all its words) and the many ways this can manifest in the language. I discussed this by way of an example using the Japanese ちょっと (Chotto) to illustrate.

The prevalence of homonyms leads to various possible complications when applied to eDiscovery.

For example, the most common is the way in which typos occur in Japanese.

In English, a typo is fairly easily discernible, based on context, since it involves simply a misplaced or omitted letter.

- Recoggnize

- Prblem

- Maiintenance

An English speaker can easily identify what word was intended by the writer.

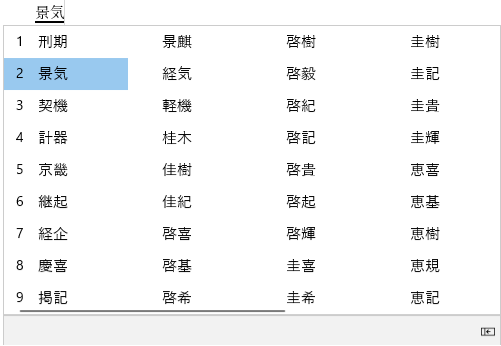

Japanese can be far more challenging, because of the way typing works. In Japanese, a person starts by typing out how the word sounds. Then, the computer pulls up a list of every homonym for that word, giving you a choice of which word to select, like this:

As I noted in Part I, as Japanese contains a huge number of homonyms, a single word can have dozens of possible homonyms—the word “Keiki” listed above has no fewer than 60 possible different choices, each with a different meaning.

The words can bear absolutely no relation to each other in meaning, for example 景気 (Keiki) means “economic conditions” while 刑期 means “length of sentence,” 計器 means “measuring equipment.”

What this means is that a “typo” in Japanese can result words that bear no relation to each other in meaning but can be inserted accidentally. This can be particularly prevalent in casual written conversation, such as text messaging. Imagine this in the context of an eDiscovery-based document review of Japanese! I’ve managed tens of thousands of hours of foreign language document review mostly with The CJK Group document, so I’ve literally seen it all.

To add to the confusion, a Japanese writer may misspell the word entirely, thus writing a word that sounds like the intended word. For example, if the person meant to write “Keiki” (Measuring equipment) they may accidentally type “Keika” and choose one of a dozen or more choices, thus to completely alter the intended meaning of the sentence.

As such, typos can add a great deal more confusion in interpretation for the reader in Japanese than a typo in English.

Homonyms & eDiscovery: What’s the Fuss All About?

This is a very common issue faced by eDiscovery reviewers when viewing emails and text messages in real world circumstances. Reading the sentence within the context of the conversation, reviewers will determine what homonym was most likely intended by the writer. Or, alternatively, if no homonym to the word makes any sense, the reviewer will try to figure out what kind of typo the writer did and try to identify what other similarly sounding word was intended.

But in rare circumstances, particularly in the context of criminal investigations, the possibility that an “odd sounding” typo may represent some other form of coded language may need to be considered as well.

This is one thing that makes applications of machine translation extremely difficult as applied to Japanese.

Due to the higher cost of eDiscovery review teams with expertise in foreign language the possibility of cutting costs by having an English language review team review documents translated from a foreign language through machine translation is often referenced.

Even the best machine learning AI will have difficulty correctly identifying a typo, much less identify the correct intended meaning based on context. Nor will it be able to flag a typo as “suspicious.”

Only a team of experts deeply versed in both the cultural and linguistic nature of a foreign language can handle these challenges with consistency. And particularly, in a language like Japanese, it can be all but essential.